The Nonstop, 24-7 CEO Salesman | Printer-friendly version

Pat Cavanaugh sells more than just about anyone in his industry and manages a fast-growing company at the same time. What's his secret? A personal discipline that lets him make the most of every waking moment. And we mean every waking moment

"The most intense part of my day is 4 in the morning," says Pat Cavanaugh. That's when he forces himself out of his king-size bed to begin his daily workout. At least he does on most days. But Thursday, April 13, was no ordinary day for the CEO of Cavanaugh Promotions -- the Pittsburgh promotional-products business that he'd started in college and recently rechristened simply "Cavanaugh."

On that day Cavanaugh would conquer Cleveland. So he was up a little earlier than usual, 3:45 a.m. to be precise. Rock music blasting from the gym in his two-story brick house, the 33-year-old mounted his Schwinn Airdyne stationary bike for a leisurely ride. Contemplating the day ahead, Cavanaugh started pedaling faster. Soon he was flying at speeds of 80 rpm. For an encore, he bench-pressed 300 pounds and hit the ground for 600 sit-ups.

With 127 miles between Cavanaugh and Cleveland, there wasn't a moment to waste. After gulping down a protein shake, he was out the door at 5:30 a.m., headed for the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Cavanaugh, who possesses a no-nonsense handsomeness, wore a black suit as well as a black watch bearing the Lexus logo, which incidentally matched his black Lexus sports utility vehicle. Both his watch and his car clock were set 15 minutes fast. He turned on the radio and popped open his Day-Timer. The seven-by-nine-inch black book is the key to his kingdom. He looked down at his jam-packed schedule. His first appointment: 8 a.m. with Jones Day Reavis & Pogue, a large law firm. That was followed by nine more appointments. Friday, the 14th, would be just as hectic -- 11 presentations in 11 hours. His prospects ran the gamut from Fortune 500 companies to the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, which wanted to talk about "unique miniature toilet-bowl items."

Cavanaugh recounts, "We were running to our cars to make the next appointment." By we, he means himself and the five uninitiated and slightly dehydrated Cavanaugh sales reps who were taking their first road trip with the CEO in Cleveland. By the end of it they would understand the meaning of a sales blitz Pat Cavanaugh-style.

Sales blitz? It was more like an Ironman competition. Imagine your salespeople dashing from one sales appointment to the next for 10 hours straight. Then imagine yourself doing the same. The final score: 114 sales presentations in two days. (See "Cavanaugh Does Cleveland," below.)

The Cleveland quest was just one more endurance test for Cavanaugh, who in the first three months of this year opened 100 new accounts, or about one a day. On the personal side, he runs a five-minute mile. He also happens to be a former NBA hopeful who traded his hoop dreams for a shot at the record books in an old-fashioned but highly competitive industry. (It hasn't changed much since Jasper Freemont Meek first slapped promotional "covers" on the backs of nearly every horse in Coshocton, Ohio, in the 1880s.)

These days the onetime basketball star doesn't have much time to spend on the court, aside from shooting baskets with his two young sons. The car-bound Cavanaugh complains of a chronic case of "cell-phone elbow." At the moment his body fat is higher than he wants it to be. But by all outward appearances, he's in great physical shape. And when it comes to selling, he's in a league of his own. Cavanaugh is not only founder and CEO of his 35-person company; he's also its #1 salesperson. What's more, he single-handedly outsells about 80% of the 20,000 companies in his field, which encompasses all manner of embroidered, minted, imprinted, and otherwise branded stuff.

Having burst on the scene full-time just seven years ago, Cavanaugh brought in $3.5 million of his company's $6.2 million in revenues last year. He makes it clear that his personal goal is to sell $5 million or $6 million a year while he builds a $100-million company over the next decade. If he can pull off the double feat, he's got a shot at making the industry's top 10.

At the heart of his balancing act is that well-worn two-page-per-day Day-Timer. And it isn't just his own Day-Timer that's crucial -- 25 of his 35 employees are required to carry one. Writing down lists of goals and assignments is more effective than putting them in the computer, Cavanaugh believes, and makes missing a deadline more painful. Everyone at the company can recite Cavanaugh's "two-day rule" for completing tasks. And lest you forget what you've promised to accomplish Monday morning, Cavanaugh leaves you a voice-mail reminder Sunday night. In his Day-Timer, he writes abbreviated to-do lists for key employees. In his car he's constantly on the phone checking employees' progress. The hard-driving CEO, who once considered a career in the military and attended West Point Prep, even regulates his staffers' downtime: every employee must take a "goof off" day once a quarter.

Cavanaugh's enthusiasm for sales dates back to his youth in Grove City, Pa., an hour outside Pittsburgh. At the age of 10 he launched his career by selling flower seeds door-to-door. Next he took orders for shoes door-to-door. One day a letter arrived from the shoemaker, asking the boy to be its Pennsylvania sales manager. "They didn't know I was just 10," he says.

Between sales calls he threw himself into sports. Years later at the University of Pittsburgh, he was a "walk-on" in basketball; he hadn't been recruited but proved himself on the court and earned a scholarship playing point guard for the Panthers in Division I competition. When he wasn't glued to a hoop, he worked on commission for an uncle who owned a promotional-products business. At 21 he started his own company. But after he graduated from college, Cavanaugh Promotions remained a part-time venture while its founder earned an M.B.A. and -- against the odds -- went out for the NBA.

Wrangling an invitation to an NBA tryout was, he says, an object lesson in how to win friends and influence people. Cavanaugh, who is six-foot-two, had an agent but quickly learned to market himself. "I'd get on the phone too and send teams my tapes," he says. "And then you've got to perform when you get the chance."

The Game Plan

Keep the initial phone call as short as possible.

Make 'em laugh.

Don't try to get more than permission to "maybe" call again.

Call again and get a meeting in person.

He got the chance in tryouts for the Denver Nuggets, Philadelphia 76ers, and Orlando Magic. "In the NBA I tried out three times," he says. The last cut was Orlando in October 1993. He wrestled with the big question: try again next season or move on? This was the man who as a kid had shoveled snow off the court in 20-degree weather so he could practice when the gyms were closed. "At that time all I wanted to do was make that damn team," he recalls. But in the back of his mind he was also thinking, "Who's going to run the business?"

At the end of the year he walked away from his hopes of a career in professional basketball for good. "It was the toughest decision I ever had to make," he says.

But he picked himself up and began to concentrate full-time on Cavanaugh Promotions. The challenge of getting a sales appointment wasn't so different from getting an invitation to an NBA tryout. In the beginning he worked on the basics. He figured out the best times to reach people on the phone and scheduled his days accordingly. Still, telephone selling wasn't easy. People would routinely cut him off, curse at him, and slam down the phone. It was then that he began formulating the game plan he still uses today and passes on to his new sales reps: (1) Keep the initial phone call as short as possible. (2) Make 'em laugh. (3) Don't try to get more than permission to "maybe" call again. (4) Call again and get a meeting in person.

In the promotions industry, recruiting sales help was a challenge, too. "Trinket salesmen," they used to be called. "I had this image of people selling out of a suitcase from the trunk of their cars," recalls Mark Algeri, who is now Cavanaugh's #2 salesperson. "Pat sold me on his high goals and vision." Hang on for the ride, the CEO said, and we'll build an organization second to none for customer service.

Together, Cavanaugh and Algeri racked up first-year sales of $226,000 in 1994. Net profits were 18%. But 1996 was the year that put Cavanaugh Promotions on the map. Pennzoil Co. commissioned a huge Super Bowl promotion for its Jiffy Lube chain. Soon after, two tons of footballs arrived in 53-foot tractor-trailers at Cavanaugh headquarters. Putting the deal together had required getting buy-in from hundreds of individual Jiffy Lube store owners. The $300,000 order catapulted the company over the $1-million mark.

In 1997 Cavanaugh himself surpassed $1 million in individual sales. That year, the four-employee company scored another victory that took it further away from the realm of trinket salesmen. A customer, 84 Lumber Co., in the town of Eighty Four, Pa., wanted to upgrade its promotional clothing. Cavanaugh and Algeri came up with the idea of private-labeling every item with "84 Gear." The new label included the company's Web address. Within six months 84 Lumber was one of Cavanaugh Promotions' largest accounts.

"When I do nothing but get on the phone, I can make 200 calls in a day."

While the industry grew 11% in 1998, Cavanaugh Promotions racked up a 70% increase in revenues -- hitting $4.6 million in sales. That landed it the #104 spot on the 1999 Inc. 500 list of America's fastest-growing private companies. But again its founder was feeling his mortal limits. "There were days in basketball when I would have to say, 'Pat, you can't work out today. You have to take a day off,'" he recalls. It was the same in business.

But in the end the choice between sales and administration was no contest. Last year Cavanaugh hired his first managers in sales, marketing, and operations. And he more than doubled his support staff, from 6 to 16. All the things he once handled himself -- from writing follow-up letters to interested prospects to making sure orders went out on time -- were now handled by his team of specialists. It all paid off late last year, when Cavanaugh captured the first of several high-level accounts. Alcan Aluminum picked Cavanaugh to be its U.S. supplier after a rigorous on-site inspection. "I could never have done this on my own," says Cavanaugh.

Cavanaugh's daily sales regimen rivals the intensity of his morning workout. "When I do nothing but get on the phone, I can make 200 calls in a day," he says matter-of-factly. Most of the company's sales begin over the phone; it does almost no advertising. On a typical weekday, Cavanaugh arrives in the office by 6:30 a.m. But unlike many CEOs, he says his first order of business is attending to his own sales prep work. "Pat controls his day, and not the other way around," says Brian Tony, who left a large health insurer to join Cavanaugh as chief operating officer last November. He describes his COO duties this way: "My main responsibility is to allow Pat to focus on sales."

By the CEO's calculations, you've got to make contact with at least 50 new prospective customers each week to excel in his business. Leaving a voice-mail message doesn't count. It's got to be live contact. Furthermore, he expects his reps to make 10 face-to-face presentations a week. And finally, 5 new sales. Cavanaugh's 50-10-5 formula sounds simple, and it is, until you consider how many calls you have to make to actually reach 50 people. And the 50% sales-conversion rate? Well, it's aggressive. But Cavanaugh points to 30-year-old Algeri, who's closed more than 50% of his face-to-face sales calls for five years now. "It's a proven system," Cavanaugh tells the new salespeople. "Do this for four or five years, and you'll succeed."

It's not easy for everyone, he concedes. One look at the sales scoreboard -- posted near the office kitchen -- makes that evident. During a week in May, one new rep had done $1,000 worth of business, and another had done $3,000. By contrast, Algeri had made $39,000 in sales. Cavanaugh had hit $82,000. Orders from current customers made up a nice chunk of his sales. But the company's future growth clearly depends on the CEO's ability to bring in new customers.

"Get the prospect to like you in 30 seconds, or you've blown it," advises Pat Cavanaugh.

During that fairly typical week, Cavanaugh saw 13 prospects and customers in person and placed phone calls to 100 more. He likes to make his cold calls from 9 a.m. to noon -- or even better, around 1:30 p.m. That's his favorite time to reach the most prized, hardest-to-get sales prospects on the phone -- when they're "sluggish and sedated." People who are impossible to reach simply go to the top of his "stalking list."

Take the purchasing guy at Home Depot, whom Cavanaugh had been pursuing long-distance since January. The buyer had had a few choice words for promotional products: "trinkets and trash." He told the CEO, "I hate dealing with companies like yours." But that didn't daunt Cavanaugh. After all, Home Depot already bought said trinkets and trash by the tens of thousands to use as store giveaways. Now, by Cavanaugh's estimate, 75 companies were dogging the buyer for the national store account. "He's going to pick someone," reasoned Cavanaugh. Why not him?

Hoping to catch the Home Depot manager a little more relaxed after lunch, Cavanaugh dialed the man's office again. No dice. His call went straight into voice mail -- again. The CEO decided to leave a message. It was the only one he'd leave that week. That's another one of his rules: No more than one voice-mail message per week. It's not just good etiquette; the tactic actually helps him get noticed.

Cavanaugh had better luck when he dialed the marketing director at Dick Corp., a large construction company in town. In previous conversations the director had been "very harsh on the phone; he would hardly talk," according to Cavanaugh. But on this day the man took Cavanaugh's call. The CEO was casual. "I'm going to be in your neck of the woods on Tuesday," he said. The marketing director said he couldn't meet then, but how about Thursday at 9? Cavanaugh wrote the date in his Day-Timer and hung up happy. He attributed the sudden breakthrough to a short and direct voice-mail message he'd left the week before. "Don't erase this message yet," he'd said. "I'm not wasting your time. All I'm asking for is 10 minutes in person. ..."

Nothing gets Cavanaugh as revved up as a prospect who gives him a hard time. "When someone says, 'Why should we use you?' I love rattling off the reasons," he declared as he was training two new sales reps during a lunchtime session at the company's new offices in Pittsburgh's North Hills. The new guys were practicing a phone script. The trick, of course, was to sound spontaneous. Cavanaugh played the role of the salesperson and then offered advice. "Get the prospect to like you in 30 seconds, or you've blown it," he told the new recruits. "Try to make a joke to remind them what a hassle it is to manage promotions. 'Do you have any hair left?' If you don't get a laugh, go for the jugular." By that he didn't mean make a last-ditch sales pitch. That would be suicide. He meant prepare to say good-bye.

"When the person lets out a sigh of relief -- 'Finally, this guy is getting off the phone' -- then come the killer questions. 'Oh, by the way, when's that golf tournament? Maybe I can work up some ideas.' You say it almost like an aside," Cavanaugh continued. "Let 'em know we know how to work on a budget: 'We've worked with the mayor's office and even the Secret Service. Maybe I can work on something for you.' Everything is maybe, maybe, so there's no absolute commitment." And, he reminded them, "you don't have to shoot every time you have the ball. Sometimes a sale is not in the best interests of our company."

The one-page script was simple. Four main points. But don't be deceived, said Cavanaugh. "The script is what allows you to get these damn appointments."

That's how he had recently gotten in to see Toni Holliday, then an executive assistant at Washington Penn Plastic Co. She was searching for just the right something to give to 126 clients. It was a $10,000 potential sale that could lead to more, like incentive items for 300 or so employees. But it had taken Cavanaugh months to land the appointment. ("I've been trying to get this forever" is a popular Cavanaugh refrain.) Now, wearing a sporty yellow-and-black houndstooth jacket and a conservative tie, he was finally sitting across from Holliday. Leather sample bag by his side, Cavanaugh talked up his company's work ethic. He used one of his favorite opening lines: "We've grown 2,000% in five years, mainly because we have good service, real good service." He also mentioned Cavanaugh's new Internet sales capabilities. But Holliday cut to the bottom line: "In one sentence, What makes your company different?"

That was the question Cavanaugh craved. He answered eagerly by describing in detail his company's culture and generous employee benefits. That struck a chord. Holliday mentioned some of her own company's perks. The executive assistant let down her defenses, revealing that she bought customer gifts in the spring and fall. "Well, I've got a few things I'd like to show you," Cavanaugh said. From the embroidered denim shirt to the sleek stainless-steel Fossil watch, there was an art to how he presented each item for her inspection. She laughed in delight at something called the Fun Floating Logo Liquid Motion Mouse Pad. "I've got to show this to my boss. This is going to make me look good," she said.

She quizzed Cavanaugh on some pricing. Satisfied with his answers, Holliday let him in on a secret: she's not satisfied with her current promotional-products supplier. There was the matter of an expensive pen that kept falling apart in customers' hands. "This would never happen with us," Cavanaugh said, examining the pen. Now they were on the same page, searching for a truly quality memento to impress customers with. They flipped through a catalog of classic-looking desk clocks, and she asked him to follow up with a quote for one art-deco-style model. He jotted it down in his Day-Timer and carefully repacked his bag. He left her office jubilant.

"Her whole tone changed in 20 minutes," he said in the parking lot. "It's like being on the basketball court. Guys are on top of you until they see you can dribble. Then they back up."

It's not that Pat Cavanaugh is a hotshot or particularly gregarious or gifted in the oratory department. It's OK to stutter a little, he tells sales reps practicing the phone script. "Be human," he stresses.

"You don't have to shoot every time you have the ball. Sometimes a sale is not in the best interests of our company."

Many CEOs cut back their personal sales as they build a sales force. Not Cavanaugh. On that point he's passionate. His reason for remaining so physically involved in sales is simple but not what you usually hear from top executives. Many CEOs stress the importance of staying in front of customers to garner additional sales and market research. But for Cavanaugh it's much more personal than that. He sells because it keeps him "competitive and sharp." There's another reason that speaks to the coach in Cavanaugh. You do it, he says, "because it helps you understand the challenges of your salespeople."

If it seems as if the CEO is running some sort of training camp for would-be sales stars, he is. His goal is to turn average reps into million-dollar sellers. In business, as in basketball, he's the player who keeps his eye on the whole court. And he believes completely in his vision.

From the beginning, Pat Cavanaugh has been laying the foundation for something much more substantial than merely selling caps, clocks, watches, and windbreakers. Rudy Frank, the manager of corporate advertising at Kennametal, a tool manufacturer headquartered in Latrobe, Pa., says he knew the little company that cold-called him five years ago had the potential to one day manage all his promotional business. And that's exactly what's happened. After 15 years on-site, the Kennametal company store -- serving 13,000 employees worldwide -- is now run by Cavanaugh and includes online sales. The store is expected ultimately to generate sales of $1 million a year.

"And I knew from day one Cavanaugh wanted that," says Frank.

Still, to hit the ultimate goal of $100 million in sales, the Cavanaugh company will have to net about 100 more accounts just like Kennametal. Pat Cavanaugh knows he personally can't keep up that sales pace forever. But for now he can. Which is why he was battling traffic on a sunny Friday afternoon to make his last sales appointment of the week. "This could be really huge," he was saying. He looked down the road, hoping to find a faster way to his destination. "Every moment counts right about now," he murmured.

Pat Cavanaugh sells more than just about anyone in his industry and manages a fast-growing company at the same time. What's his secret? A personal discipline that lets him make the most of every waking moment. And we mean every waking moment

"The most intense part of my day is 4 in the morning," says Pat Cavanaugh. That's when he forces himself out of his king-size bed to begin his daily workout. At least he does on most days. But Thursday, April 13, was no ordinary day for the CEO of Cavanaugh Promotions -- the Pittsburgh promotional-products business that he'd started in college and recently rechristened simply "Cavanaugh."

On that day Cavanaugh would conquer Cleveland. So he was up a little earlier than usual, 3:45 a.m. to be precise. Rock music blasting from the gym in his two-story brick house, the 33-year-old mounted his Schwinn Airdyne stationary bike for a leisurely ride. Contemplating the day ahead, Cavanaugh started pedaling faster. Soon he was flying at speeds of 80 rpm. For an encore, he bench-pressed 300 pounds and hit the ground for 600 sit-ups.

With 127 miles between Cavanaugh and Cleveland, there wasn't a moment to waste. After gulping down a protein shake, he was out the door at 5:30 a.m., headed for the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Cavanaugh, who possesses a no-nonsense handsomeness, wore a black suit as well as a black watch bearing the Lexus logo, which incidentally matched his black Lexus sports utility vehicle. Both his watch and his car clock were set 15 minutes fast. He turned on the radio and popped open his Day-Timer. The seven-by-nine-inch black book is the key to his kingdom. He looked down at his jam-packed schedule. His first appointment: 8 a.m. with Jones Day Reavis & Pogue, a large law firm. That was followed by nine more appointments. Friday, the 14th, would be just as hectic -- 11 presentations in 11 hours. His prospects ran the gamut from Fortune 500 companies to the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District, which wanted to talk about "unique miniature toilet-bowl items."

Cavanaugh recounts, "We were running to our cars to make the next appointment." By we, he means himself and the five uninitiated and slightly dehydrated Cavanaugh sales reps who were taking their first road trip with the CEO in Cleveland. By the end of it they would understand the meaning of a sales blitz Pat Cavanaugh-style.

Sales blitz? It was more like an Ironman competition. Imagine your salespeople dashing from one sales appointment to the next for 10 hours straight. Then imagine yourself doing the same. The final score: 114 sales presentations in two days. (See "Cavanaugh Does Cleveland," below.)

The Cleveland quest was just one more endurance test for Cavanaugh, who in the first three months of this year opened 100 new accounts, or about one a day. On the personal side, he runs a five-minute mile. He also happens to be a former NBA hopeful who traded his hoop dreams for a shot at the record books in an old-fashioned but highly competitive industry. (It hasn't changed much since Jasper Freemont Meek first slapped promotional "covers" on the backs of nearly every horse in Coshocton, Ohio, in the 1880s.)

These days the onetime basketball star doesn't have much time to spend on the court, aside from shooting baskets with his two young sons. The car-bound Cavanaugh complains of a chronic case of "cell-phone elbow." At the moment his body fat is higher than he wants it to be. But by all outward appearances, he's in great physical shape. And when it comes to selling, he's in a league of his own. Cavanaugh is not only founder and CEO of his 35-person company; he's also its #1 salesperson. What's more, he single-handedly outsells about 80% of the 20,000 companies in his field, which encompasses all manner of embroidered, minted, imprinted, and otherwise branded stuff.

Having burst on the scene full-time just seven years ago, Cavanaugh brought in $3.5 million of his company's $6.2 million in revenues last year. He makes it clear that his personal goal is to sell $5 million or $6 million a year while he builds a $100-million company over the next decade. If he can pull off the double feat, he's got a shot at making the industry's top 10.

At the heart of his balancing act is that well-worn two-page-per-day Day-Timer. And it isn't just his own Day-Timer that's crucial -- 25 of his 35 employees are required to carry one. Writing down lists of goals and assignments is more effective than putting them in the computer, Cavanaugh believes, and makes missing a deadline more painful. Everyone at the company can recite Cavanaugh's "two-day rule" for completing tasks. And lest you forget what you've promised to accomplish Monday morning, Cavanaugh leaves you a voice-mail reminder Sunday night. In his Day-Timer, he writes abbreviated to-do lists for key employees. In his car he's constantly on the phone checking employees' progress. The hard-driving CEO, who once considered a career in the military and attended West Point Prep, even regulates his staffers' downtime: every employee must take a "goof off" day once a quarter.

Cavanaugh's enthusiasm for sales dates back to his youth in Grove City, Pa., an hour outside Pittsburgh. At the age of 10 he launched his career by selling flower seeds door-to-door. Next he took orders for shoes door-to-door. One day a letter arrived from the shoemaker, asking the boy to be its Pennsylvania sales manager. "They didn't know I was just 10," he says.

Between sales calls he threw himself into sports. Years later at the University of Pittsburgh, he was a "walk-on" in basketball; he hadn't been recruited but proved himself on the court and earned a scholarship playing point guard for the Panthers in Division I competition. When he wasn't glued to a hoop, he worked on commission for an uncle who owned a promotional-products business. At 21 he started his own company. But after he graduated from college, Cavanaugh Promotions remained a part-time venture while its founder earned an M.B.A. and -- against the odds -- went out for the NBA.

Wrangling an invitation to an NBA tryout was, he says, an object lesson in how to win friends and influence people. Cavanaugh, who is six-foot-two, had an agent but quickly learned to market himself. "I'd get on the phone too and send teams my tapes," he says. "And then you've got to perform when you get the chance."

The Game Plan

Keep the initial phone call as short as possible.

Make 'em laugh.

Don't try to get more than permission to "maybe" call again.

Call again and get a meeting in person.

He got the chance in tryouts for the Denver Nuggets, Philadelphia 76ers, and Orlando Magic. "In the NBA I tried out three times," he says. The last cut was Orlando in October 1993. He wrestled with the big question: try again next season or move on? This was the man who as a kid had shoveled snow off the court in 20-degree weather so he could practice when the gyms were closed. "At that time all I wanted to do was make that damn team," he recalls. But in the back of his mind he was also thinking, "Who's going to run the business?"

At the end of the year he walked away from his hopes of a career in professional basketball for good. "It was the toughest decision I ever had to make," he says.

But he picked himself up and began to concentrate full-time on Cavanaugh Promotions. The challenge of getting a sales appointment wasn't so different from getting an invitation to an NBA tryout. In the beginning he worked on the basics. He figured out the best times to reach people on the phone and scheduled his days accordingly. Still, telephone selling wasn't easy. People would routinely cut him off, curse at him, and slam down the phone. It was then that he began formulating the game plan he still uses today and passes on to his new sales reps: (1) Keep the initial phone call as short as possible. (2) Make 'em laugh. (3) Don't try to get more than permission to "maybe" call again. (4) Call again and get a meeting in person.

In the promotions industry, recruiting sales help was a challenge, too. "Trinket salesmen," they used to be called. "I had this image of people selling out of a suitcase from the trunk of their cars," recalls Mark Algeri, who is now Cavanaugh's #2 salesperson. "Pat sold me on his high goals and vision." Hang on for the ride, the CEO said, and we'll build an organization second to none for customer service.

Together, Cavanaugh and Algeri racked up first-year sales of $226,000 in 1994. Net profits were 18%. But 1996 was the year that put Cavanaugh Promotions on the map. Pennzoil Co. commissioned a huge Super Bowl promotion for its Jiffy Lube chain. Soon after, two tons of footballs arrived in 53-foot tractor-trailers at Cavanaugh headquarters. Putting the deal together had required getting buy-in from hundreds of individual Jiffy Lube store owners. The $300,000 order catapulted the company over the $1-million mark.

In 1997 Cavanaugh himself surpassed $1 million in individual sales. That year, the four-employee company scored another victory that took it further away from the realm of trinket salesmen. A customer, 84 Lumber Co., in the town of Eighty Four, Pa., wanted to upgrade its promotional clothing. Cavanaugh and Algeri came up with the idea of private-labeling every item with "84 Gear." The new label included the company's Web address. Within six months 84 Lumber was one of Cavanaugh Promotions' largest accounts.

"When I do nothing but get on the phone, I can make 200 calls in a day."

While the industry grew 11% in 1998, Cavanaugh Promotions racked up a 70% increase in revenues -- hitting $4.6 million in sales. That landed it the #104 spot on the 1999 Inc. 500 list of America's fastest-growing private companies. But again its founder was feeling his mortal limits. "There were days in basketball when I would have to say, 'Pat, you can't work out today. You have to take a day off,'" he recalls. It was the same in business.

But in the end the choice between sales and administration was no contest. Last year Cavanaugh hired his first managers in sales, marketing, and operations. And he more than doubled his support staff, from 6 to 16. All the things he once handled himself -- from writing follow-up letters to interested prospects to making sure orders went out on time -- were now handled by his team of specialists. It all paid off late last year, when Cavanaugh captured the first of several high-level accounts. Alcan Aluminum picked Cavanaugh to be its U.S. supplier after a rigorous on-site inspection. "I could never have done this on my own," says Cavanaugh.

Cavanaugh's daily sales regimen rivals the intensity of his morning workout. "When I do nothing but get on the phone, I can make 200 calls in a day," he says matter-of-factly. Most of the company's sales begin over the phone; it does almost no advertising. On a typical weekday, Cavanaugh arrives in the office by 6:30 a.m. But unlike many CEOs, he says his first order of business is attending to his own sales prep work. "Pat controls his day, and not the other way around," says Brian Tony, who left a large health insurer to join Cavanaugh as chief operating officer last November. He describes his COO duties this way: "My main responsibility is to allow Pat to focus on sales."

By the CEO's calculations, you've got to make contact with at least 50 new prospective customers each week to excel in his business. Leaving a voice-mail message doesn't count. It's got to be live contact. Furthermore, he expects his reps to make 10 face-to-face presentations a week. And finally, 5 new sales. Cavanaugh's 50-10-5 formula sounds simple, and it is, until you consider how many calls you have to make to actually reach 50 people. And the 50% sales-conversion rate? Well, it's aggressive. But Cavanaugh points to 30-year-old Algeri, who's closed more than 50% of his face-to-face sales calls for five years now. "It's a proven system," Cavanaugh tells the new salespeople. "Do this for four or five years, and you'll succeed."

It's not easy for everyone, he concedes. One look at the sales scoreboard -- posted near the office kitchen -- makes that evident. During a week in May, one new rep had done $1,000 worth of business, and another had done $3,000. By contrast, Algeri had made $39,000 in sales. Cavanaugh had hit $82,000. Orders from current customers made up a nice chunk of his sales. But the company's future growth clearly depends on the CEO's ability to bring in new customers.

"Get the prospect to like you in 30 seconds, or you've blown it," advises Pat Cavanaugh.

During that fairly typical week, Cavanaugh saw 13 prospects and customers in person and placed phone calls to 100 more. He likes to make his cold calls from 9 a.m. to noon -- or even better, around 1:30 p.m. That's his favorite time to reach the most prized, hardest-to-get sales prospects on the phone -- when they're "sluggish and sedated." People who are impossible to reach simply go to the top of his "stalking list."

Take the purchasing guy at Home Depot, whom Cavanaugh had been pursuing long-distance since January. The buyer had had a few choice words for promotional products: "trinkets and trash." He told the CEO, "I hate dealing with companies like yours." But that didn't daunt Cavanaugh. After all, Home Depot already bought said trinkets and trash by the tens of thousands to use as store giveaways. Now, by Cavanaugh's estimate, 75 companies were dogging the buyer for the national store account. "He's going to pick someone," reasoned Cavanaugh. Why not him?

Hoping to catch the Home Depot manager a little more relaxed after lunch, Cavanaugh dialed the man's office again. No dice. His call went straight into voice mail -- again. The CEO decided to leave a message. It was the only one he'd leave that week. That's another one of his rules: No more than one voice-mail message per week. It's not just good etiquette; the tactic actually helps him get noticed.

Cavanaugh had better luck when he dialed the marketing director at Dick Corp., a large construction company in town. In previous conversations the director had been "very harsh on the phone; he would hardly talk," according to Cavanaugh. But on this day the man took Cavanaugh's call. The CEO was casual. "I'm going to be in your neck of the woods on Tuesday," he said. The marketing director said he couldn't meet then, but how about Thursday at 9? Cavanaugh wrote the date in his Day-Timer and hung up happy. He attributed the sudden breakthrough to a short and direct voice-mail message he'd left the week before. "Don't erase this message yet," he'd said. "I'm not wasting your time. All I'm asking for is 10 minutes in person. ..."

Nothing gets Cavanaugh as revved up as a prospect who gives him a hard time. "When someone says, 'Why should we use you?' I love rattling off the reasons," he declared as he was training two new sales reps during a lunchtime session at the company's new offices in Pittsburgh's North Hills. The new guys were practicing a phone script. The trick, of course, was to sound spontaneous. Cavanaugh played the role of the salesperson and then offered advice. "Get the prospect to like you in 30 seconds, or you've blown it," he told the new recruits. "Try to make a joke to remind them what a hassle it is to manage promotions. 'Do you have any hair left?' If you don't get a laugh, go for the jugular." By that he didn't mean make a last-ditch sales pitch. That would be suicide. He meant prepare to say good-bye.

"When the person lets out a sigh of relief -- 'Finally, this guy is getting off the phone' -- then come the killer questions. 'Oh, by the way, when's that golf tournament? Maybe I can work up some ideas.' You say it almost like an aside," Cavanaugh continued. "Let 'em know we know how to work on a budget: 'We've worked with the mayor's office and even the Secret Service. Maybe I can work on something for you.' Everything is maybe, maybe, so there's no absolute commitment." And, he reminded them, "you don't have to shoot every time you have the ball. Sometimes a sale is not in the best interests of our company."

The one-page script was simple. Four main points. But don't be deceived, said Cavanaugh. "The script is what allows you to get these damn appointments."

That's how he had recently gotten in to see Toni Holliday, then an executive assistant at Washington Penn Plastic Co. She was searching for just the right something to give to 126 clients. It was a $10,000 potential sale that could lead to more, like incentive items for 300 or so employees. But it had taken Cavanaugh months to land the appointment. ("I've been trying to get this forever" is a popular Cavanaugh refrain.) Now, wearing a sporty yellow-and-black houndstooth jacket and a conservative tie, he was finally sitting across from Holliday. Leather sample bag by his side, Cavanaugh talked up his company's work ethic. He used one of his favorite opening lines: "We've grown 2,000% in five years, mainly because we have good service, real good service." He also mentioned Cavanaugh's new Internet sales capabilities. But Holliday cut to the bottom line: "In one sentence, What makes your company different?"

That was the question Cavanaugh craved. He answered eagerly by describing in detail his company's culture and generous employee benefits. That struck a chord. Holliday mentioned some of her own company's perks. The executive assistant let down her defenses, revealing that she bought customer gifts in the spring and fall. "Well, I've got a few things I'd like to show you," Cavanaugh said. From the embroidered denim shirt to the sleek stainless-steel Fossil watch, there was an art to how he presented each item for her inspection. She laughed in delight at something called the Fun Floating Logo Liquid Motion Mouse Pad. "I've got to show this to my boss. This is going to make me look good," she said.

She quizzed Cavanaugh on some pricing. Satisfied with his answers, Holliday let him in on a secret: she's not satisfied with her current promotional-products supplier. There was the matter of an expensive pen that kept falling apart in customers' hands. "This would never happen with us," Cavanaugh said, examining the pen. Now they were on the same page, searching for a truly quality memento to impress customers with. They flipped through a catalog of classic-looking desk clocks, and she asked him to follow up with a quote for one art-deco-style model. He jotted it down in his Day-Timer and carefully repacked his bag. He left her office jubilant.

"Her whole tone changed in 20 minutes," he said in the parking lot. "It's like being on the basketball court. Guys are on top of you until they see you can dribble. Then they back up."

It's not that Pat Cavanaugh is a hotshot or particularly gregarious or gifted in the oratory department. It's OK to stutter a little, he tells sales reps practicing the phone script. "Be human," he stresses.

"You don't have to shoot every time you have the ball. Sometimes a sale is not in the best interests of our company."

Many CEOs cut back their personal sales as they build a sales force. Not Cavanaugh. On that point he's passionate. His reason for remaining so physically involved in sales is simple but not what you usually hear from top executives. Many CEOs stress the importance of staying in front of customers to garner additional sales and market research. But for Cavanaugh it's much more personal than that. He sells because it keeps him "competitive and sharp." There's another reason that speaks to the coach in Cavanaugh. You do it, he says, "because it helps you understand the challenges of your salespeople."

If it seems as if the CEO is running some sort of training camp for would-be sales stars, he is. His goal is to turn average reps into million-dollar sellers. In business, as in basketball, he's the player who keeps his eye on the whole court. And he believes completely in his vision.

From the beginning, Pat Cavanaugh has been laying the foundation for something much more substantial than merely selling caps, clocks, watches, and windbreakers. Rudy Frank, the manager of corporate advertising at Kennametal, a tool manufacturer headquartered in Latrobe, Pa., says he knew the little company that cold-called him five years ago had the potential to one day manage all his promotional business. And that's exactly what's happened. After 15 years on-site, the Kennametal company store -- serving 13,000 employees worldwide -- is now run by Cavanaugh and includes online sales. The store is expected ultimately to generate sales of $1 million a year.

"And I knew from day one Cavanaugh wanted that," says Frank.

Still, to hit the ultimate goal of $100 million in sales, the Cavanaugh company will have to net about 100 more accounts just like Kennametal. Pat Cavanaugh knows he personally can't keep up that sales pace forever. But for now he can. Which is why he was battling traffic on a sunny Friday afternoon to make his last sales appointment of the week. "This could be really huge," he was saying. He looked down the road, hoping to find a faster way to his destination. "Every moment counts right about now," he murmured.

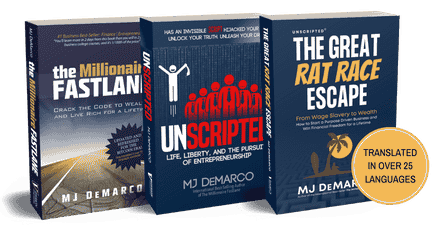

Dislike ads? Become a Fastlane member:

Subscribe today and surround yourself with winners and millionaire mentors, not those broke friends who only want to drink beer and play video games. :-)

Membership Required: Upgrade to Expose Nearly 1,000,000 Posts

Ready to Unleash the Millionaire Entrepreneur in You?

Become a member of the Fastlane Forum, the private community founded by best-selling author and multi-millionaire entrepreneur MJ DeMarco. Since 2007, MJ DeMarco has poured his heart and soul into the Fastlane Forum, helping entrepreneurs reclaim their time, win their financial freedom, and live their best life.

With more than 39,000 posts packed with insights, strategies, and advice, you’re not just a member—you’re stepping into MJ’s inner-circle, a place where you’ll never be left alone.

Become a member and gain immediate access to...

- Active Community: Ever join a community only to find it DEAD? Not at Fastlane! As you can see from our home page, life-changing content is posted dozens of times daily.

- Exclusive Insights: Direct access to MJ DeMarco’s daily contributions and wisdom.

- Powerful Networking Opportunities: Connect with a diverse group of successful entrepreneurs who can offer mentorship, collaboration, and opportunities.

- Proven Strategies: Learn from the best in the business, with actionable advice and strategies that can accelerate your success.

"You are the average of the five people you surround yourself with the most..."

Who are you surrounding yourself with? Surround yourself with millionaire success. Join Fastlane today!

Join Today