- Joined

- Aug 2, 2017

- Messages

- 346

Rep Bank

$1,565

$1,565

User Power: 307%

"For if one removes from our experiences everything that belongs to the senses, there still remain certain original concepts and the judgments generated from them, which must have arisen entirely a priori, independently of experience, because they make one able to say more about the objects that appear to the senses than mere experience would teach, or at least make one believe that one can say this, and make assertions contain true universality and strict necessity, the likes of which merely empirical cognition can never afford."

That's from Critique of Pure Reason. It's wrong, of course: all concepts originally arise from the senses. The point is, how could a guy who believes that 'a priori' is valid do anything to defend objectivity in any form? A priori is the antithesis of objectivity.

Alright. Your next step is to justify the bolded assertion, to say why it is true and/or why anyone should believe you. You have two options for this.

You can hold it up as true, doing your own little bit of metaphysics. But that looks an awful lot like a priori knowledge.

You can be a good empiricist and leave it up to observation. But then you'll have to say what individual observation or observations can justify the universal assertion.

Before you answer, keep in mind that -- if you read the preface to the First Critique -- this dilemma, between dogmatic rationalism and skeptical empiricism, is exactly what motivated Kant to write the Critiques. The transcendental philosophy was meant to be a way to salvage scientific knowledge and human freedom given that we can't just speculate about the nature of being, the way the ancient Greeks and the medieval Christians were wont to do.

The basic problem is that if you have concepts without any basis in sensation, you're just chattering to yourself. If you look at the senses alone, then you give up on lots of things you need -- universal generalizations, logical inference, numbers, mathematical reasoning. (Hume saw this and bit the bullet, but most people today don't want to think that causality is just a fabrication of the mind, given what we know about physics.)

As far as the question of a prioricity and objectivity, it looks like you've confused objectivity with realism. A priori doesn't mean subjective, it just means prior to experience. An a priori claim would be something as trivial as "2 + 2 = 4". The expression is universally true, and true regardless of what anyone believes, which is all that objectivity entails.

If you want to talk about whether numbers and mathematical equations are "real" in the way a coffee cup or a star is real, well, that's a different issue.

Kant's moral standards were based on "Duty", which is an entirely non-objective concept. Duty is the idea that you have a moral obligation to do something regardless of whether you want to, regardless whether you receive a reward from it, regardless of whether it is good for you or bad for you. The source of the moral obligation? Always goes back to 'laws of society' in his writing.

Nothing about this is right.

Let's take a step back because we're missing some key background. The books are called *critiques* for a reason. He's investigating what is necessary for different kinds of thought, where the limits lie.

The First Critique is concerned with the limits and possibilites of theoretical knowledge. Physical objects, properties, cause and effect, that kind of thing. The world available to the senses and to the theoretical intellect is a world of cause and effect.

One of the surprising conclusions is that practical thinking, which concerns action, freedom and morality, deals with thing that fall outside the scope of theoretical reasoning.

Morality falls on the practical sides, concerning freedom and rational necessity, not physical objects and causality.

Turning specifically to the moral theory, a duty cannot be non-objective because as far as Kant is concerned, a moral obligation is a universal command which holds come what may. If one ought not tell a lie, then one is obliged not to lie no matter what time it is, where you are, or whether there's an axe murderer ready to kill your best friend if you don't lie to him.

In the Preface to the Groundwork we have this rather unwieldy sentence:

"Thus, among practical cognitions, not only do moral laws, along with their principles, differ essentially from all the rest, in which there is something empirical, but all moral philosophy is based entirely on its pure part; and when it is applied to the human being it does not borrow the least thing from acquaintance with him (from anthropology) but gives to him, as a rational being, laws a priori, which no doubt still require a judgment sharpened by experience...for the human being is affected by so many inclinations that, though capable of the idea of a practical pure reason, he is not so easily able to make it effective in concreto in the conduct of his life."

Nobody said he was a great writer. For those not comfy with stilted German, the point of this passage is that moral laws are not empirical but pure -- which means, formal or logical, purely rational rather than having anything to do with the specific person or circumstances. The moral law is a matter of pure rationality, which has nothing to do with feelings, emotions, desires, or sensations.

I'm not sure why you'd think this is somehow non-objective, or in any way connected to the laws of society. He's distanced himself about as far as you can distance yourself from subjective or social justifications. This morality is more like math or logic than feelings or social norms. (Which is ironically one of the complaints to make about Kantian moral theory.)

From another angle, consider the opening sentence from Section I of the Groundwork:

"It is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, that could be considered good without limitation except a good will."

Kant goes on to write that moral goodness concerns who you are, in so far as what you desire and wish is the true test of a person's character. But he also realizes that human beings are really pretty messed up (the "crooked timber" quote) and saddled with so many competing motives that we need reason to even speak of moral behavior. Reason has to be separated to the maximal extent possible from the "animal" motivations.

Needless to say, reason is *not* a matter of social laws. In fact this is one of the most famous things about Kant's moral theory (Groundwork Section I again):

"But what kind of law can that be, the representation of which must determine the will, even without regard for the effect expected from it, in order for the will to be called good absolutely and without limitation? Since I have deprived the will of every impluse that could arise for it from obeying some law, nothing is left but the conformity of actions as such with universal law, which alone is to serve the will as its principle, that is, I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law."

The moral law transcends my impulses, your impulses, the rules and norms and laws of society. The moral law is universal.

He even claimed that, if you get a reward for an action, it's not virtuous, ie. Working hard to build a business is not virtuous if you do it to make money. However if you do it out of a sense of duty to donate all your money to charity, it IS virtuous.

Kant did say that an action couldn't be moral if you did it for a reward or because it made you feel good, or for any reason other than the motive of moral duty. To be fair, his stubbornness on this point gets him into trouble.

That said, to put it this way confuses moral duty and moral blame. Kant wouldn't say that an entrepreneur who works hard to build a business is therefore bad because not acting out of a moral motive. He's surprisingly restrained as far as what counts as moral actions, and most of the things we do fall outside that circle.

Unless you're expressly acting against moral duty, the action has no moral significance, good or bad. Entrepreneurship wouldn't be a moral issue at all unless somebody was acting like a dirtbag.

Don't get it twisted. Kant was pure evil. Why do you think these guys love him so much?

They even get a child to yell: "Read Kant, Cunt!". Do those people look familiar to you? They're the epitome of the PC Police.

Kant's motive from the beginning was always to convince people that they were incapable of understanding reality so that they would become mindlessly obedient followers - not for any real purpose; he just hated mankind. He wanted them to feel like their own desires had no value, which at the end of the day, implies that THEY have no value. Here's another quote by that POS. Think about it.

I'm curious...have you actually read Kant or are you recycling complaints you've picked up from second and third hand Youtubers? Virtually nothing you've said is accurate. It's like you're talking about an entirely different writer.

I can understand seeing crappy people holding up a writer's work and having an emotional reaction to it. If that's your worry, then the problem is crappy people and their sloppy thinking.

I'm not sure that countering that with more sloppy thinking and screaming-teenager name calling is really the antidote.

If anything it should be a good reminder that we need to be skeptical about anything unless you've spent time studying the texts yourself. Which means really spending time with them, not the sloppy way that so many public figures are sloppy with ideas.

Dislike ads? Become a Fastlane member:

Subscribe today and surround yourself with winners and millionaire mentors, not those broke friends who only want to drink beer and play video games. :-)

Membership Required: Upgrade to Expose Nearly 1,000,000 Posts

Ready to Unleash the Millionaire Entrepreneur in You?

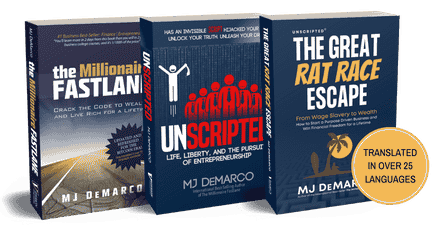

Become a member of the Fastlane Forum, the private community founded by best-selling author and multi-millionaire entrepreneur MJ DeMarco. Since 2007, MJ DeMarco has poured his heart and soul into the Fastlane Forum, helping entrepreneurs reclaim their time, win their financial freedom, and live their best life.

With more than 39,000 posts packed with insights, strategies, and advice, you’re not just a member—you’re stepping into MJ’s inner-circle, a place where you’ll never be left alone.

Become a member and gain immediate access to...

- Active Community: Ever join a community only to find it DEAD? Not at Fastlane! As you can see from our home page, life-changing content is posted dozens of times daily.

- Exclusive Insights: Direct access to MJ DeMarco’s daily contributions and wisdom.

- Powerful Networking Opportunities: Connect with a diverse group of successful entrepreneurs who can offer mentorship, collaboration, and opportunities.

- Proven Strategies: Learn from the best in the business, with actionable advice and strategies that can accelerate your success.

"You are the average of the five people you surround yourself with the most..."

Who are you surrounding yourself with? Surround yourself with millionaire success. Join Fastlane today!

Join Today